Questions & Answers

Which diseases is BPRC helping combat? Why is animal testing involving primates still necessary? Are there any alternatives? What kind of lives do these primates lead at your place?

We can imagine that you would like to receive a clear answer to all these questions. Therefore, we feel it is our duty to provide you with clear and thorough information.

We have subdivided the questions and answers into the five subcategories below. These subcategories present the answers to the questions we have been asked most over the years. If you feel there is a question we forgot to answer, or if our answers raised some new questions for you, please send an e-mail to [email protected].

Select your question

-

About BPRC

Questions about the Biomedical Primate Research Centre (BPRC)

Deadly diseases constitute a threat to public health. Primate research centres such as BPRC contribute to the development of medications that save lives. Our scientific research institute is located in Rijswijk and employs more than one hundred people, ranging from animal care workers and animal behaviour experts to vets and geneticists.

-

Why are scientific research institutes such as BPRC necessary?In large parts of the world, people's health has improved considerably in the past century. This is not just because of improved hygiene, but is also largely due to breakthroughs in the medical industry, e.g. drugs and vaccines that were developed during this century, often partially due to animal testing. Of course there are still life-threatening diseases that cannot be prevented or cured. In order to successfully combat these diseases, we must expand our knowledge. Biomedical research forms the basis for the development of new and safe drugs and therapies.

-

So what does BPRC actually do?The Biomedical Primate Research Centre (BPRC) is a scientific research institute that conducts biomedical research on life-threatening diseases, e.g. AIDS, malaria, hepatitis, tuberculosis and autoimmune diseases such as MS. At the same time, we also expend a great deal of energy on the development of testing methods that do not involve animal testing. For this reason, every department in our institute seeks to develop alternative research methods. Moreover, there is a special unit at BPRC that carries out research on alternative methods.

But that is not all BPRC does. We also collaborate with zoos, and we contribute to the health of primates living in the wild; BPRC researchers are working hard to develop methods which will help us preserve endangered species in an animal-friendly manner. -

What role does BPRC play in research on life-threatening diseases?In its capacity as Europe's one of the largest largest non-commercial primate research centre, BPRC plays a vital part in biomedical research on serious diseases affecting humans. BPRC conducts both exploratory and applied medical research for the purpose of improving public health. The purpose of our exploratory research is to increase our knowledge of the genesis and pathogenesis of chronic and infectious diseases. The purpose of our applied research is to contribute to the development of new medications or therapies for serious diseases.

Without exception, such studies take a long time to be completed, and experiments involving primates continue to be necessary. We accommodate and look after our animals with great devotion and attention, and while we do so, we try to determine how we can change things in the future. For this reason, BPRC is very active in the development of alternative methods which do not involve animal testing.

We do not keep the results of our studies (both involving and not involving animals) to ourselves. We make all our data available to third parties through publications, for example. Besides that, our special biobank, constitutes a valuable source of information for organisations both in the Netherlands and abroad. -

Where does BPRC get the money for all this research?We prioritise animal welfare in our work. Our primates must be given as much room as they need to be themselves and move around freely. It is vital to us that they lead happy lives, which costs a considerable amount of money. In order to ensure that BPRC can properly look after its animals, BPRC receives an annual grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science.

However, the Dutch government is not the only organisation to believe in our work. We also receive financial support from international governmental organisations and charities. The best-known foundations which believe in our work are the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research. -

Why does BPRC receive government support?Non-human primates are definitely not used for biomedical research as a matter of course. Quite the contrary, actually. They are only used if no suitable alternatives are available. However, for the time being, this type of research will continue to be needed to eradicate serious diseases. For this reason, the government uses services provided by specialist primate research centres, such as BPRC, where loving care for laboratory animals and science go hand in hand.

-

Can I come and see for myself what BPRC is like?You are welcome to come and see us at BPRC. Upon request (through e-mail), we will give schools, students and other interested parties a tour of our premises. (Many reports of such visits can be found on the Internet.) We often receive visits from ministers, state secretaries and other policy makers, who are welcome guests at BPRC. In addition, we have regularly scheduled open days for locals and family members and acquaintances of our employees. Our centre receives over 600 visitors per year.

-

What is BPRC doing to remain relevant in the future?BPRC prioritises quality over quantity. We demonstrate this in several ways. For instance, we try to obtain more information from fewer animals, meaning we will need fewer animals for testing purposes. In addition, we expend a great deal of energy on identifying ways to conduct research that do not involve animal testing. Furthermore, we pay a great deal of attention to ‘ethological research’ (i.e., observation), which helps us give our primates even better living conditions. Another thing that matters to us a great deal is our research on improving the situation of endangered species living in the wild .

-

What is BPRC's organisational structure like?One specialist department is responsible for looking after the animals used in our experiments and ensuring their welfare. The scientific research departments engage in the biomedical research and pre-clinical development required to ensure that promising new medications can be safely administered to human test subjects. The people working at these departments are specialists in the fields of virology, neurobiology & aging, parasitology, genetics, ethology and alternative methods. BPRC employs well over a hundred people.

-

-

About the scientific research conducted by BPRC

Questions about the scientific research conducted by BPRC

BPRC conducts biomedical research in which primates are used as animal models that allow us to study serious diseases in humans.

-

On what kinds of diseases do BPRC's studies focus?As far as infectious diseases are concerned, we study experimental treatments of diseases such as corona, malaria, AIDS, dengue, tuberculosis and Zika virus. BPRC also conducts research designed to eradicate well-known aging diseases. These are just some of the fields of research we engage in. Furthermore, BPRC was closely involved in a study designed to improve organ transplantation methods. We store tissue and blood products in our often-consulted biobank, thus ensuring that nothing is wasted. Other researchers are welcome to use this material for their own medical research and in order to help endangered primate species living in the wild.

-

To what kinds of results has BPRC contributed?BPRC played an important part in the development of safe organ and bone marrow transplantation protocols. A vaccine against corona and a Hepatitis B vaccine that are now used worldwide have been tested within BPRC among other places. Research conducted at BPRC has significantly improved our understanding of diseases such as AIDS, arthritis and malaria. Our recent breakthroughs include the development and refinement of models used to treat Multiple Sclerosis, Parkinson's disease and tuberculosis. In addition, BPRC studies on alternative methods have demonstrated new perspectives that will help us replace, refine and reduce animal testing.

Another advantage of the tests carried out at BPRC, which should not be underestimated, is the fact that potentially 'unsafe' medications and therapies are discovered at an early stage.

An overview of the results we have obtained can be found in the booklet presenting our study results.

-

Why do we continue to need primates for biomedical research?To this day, clinical trials cannot be held without prior animal testing. After all, cells in a Petri dish can behave completely differently from cells in a living body. In a small minority of these studies, primates are the only animals suitable for experimentation. In the Netherlands the Experiments on Animals Act stipulates that primates can only be used for experimentation purposes if no other method is available.

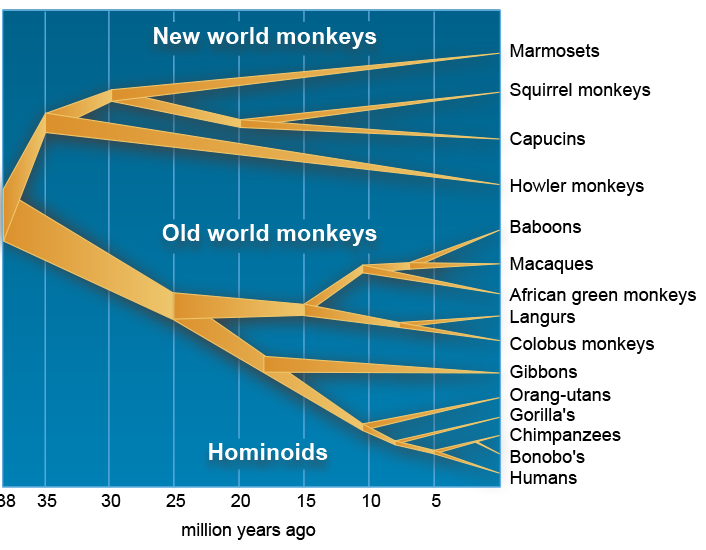

Genetically, primates are the species most similar to human beings; rhesus macaques are genetically close to 93% identical to humans. The chart below shows the various levels of genetic kinship. Certain types of primates are the only species which can be infected by the same viruses and/or parasites as humans. In addition, the latest generation of medications and therapies is highly specific and is only effective in humans or non-human primates. This means that primates are more suited to test the safety and efficacy of new vaccines, medications and treatment methods than any other species. We do not use primates lightly. We always weigh our options carefully before deciding on a primate.

The fact that governmental organisations and recognised charities such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Michael J. Fox Foundation support our research proves that we are creating added value for public health.

-

Are there viable alternatives to animal testing?The Dutch government does not allow clinical trials featuring human subjects unless the experimental method in question has been tested on animals first. While we perform those tests, we contemplate methods allowing us to conduct tests without the use of any animals. Because at the end of the day, we all want the same thing. If any alternative methods are available, we will use them. We have two reasons to do so. First, it means we do not have to make any animals uncomfortable, and secondly, the alternatives are cheaper. Unfortunately, we have not yet advanced far enough in the development of alternative research methods to be able to solve all the complex research questions. For the sake of clarity, it should be added that research centres like BPRC require authorisation granted by an ethics committee prior to embarking on any study. Among other things, this committee will assess whether all available avenues for reasonable alternatives have been explored.

-

How does BPRC define 'biomedical research'?Scientific research serving medicine. Biomedical research forms the basis for the development of new medications. Biomedical research helps us obtain knowledge which will give rise to new ideas. All of this will help us eradicate the serious diseases from which people may suffer.

-

Why does biomedical research typically take a lot of time to be completed?Conducting research on diseases can be compared to assembling a 4,000-piece jigsaw puzzle. Every study and every publication forms one piece of the puzzle. Pathogens and pathomechanisms depend on a huge number of factors that may affect their outcome. It takes many years to test every aspect and ensure that a medication is effective. In addition, pathogens mutate, causing us to have to look for new solutions.

Refer to our Annual Scientific Report for an overview of the most recent developments.

-

Are the studies conducted by BPRC subject to proper assessment?You bet! Our studies are thoroughly assessed well before we can even begin conducting them. Before embarking on a study, our specialists are required to submit each study proposal to the Animal Experiments Committee (DEC), which will then issue an independent assessment of the proposal. Studies can only be conducted if the Committee issues a positive decision, and if the Central Authority for Scientific Procedures on Animals (CCD) then issues a permit.

The quality of our research programmes is safeguarded in three ways. These are:

- supervision by a scientific advisory board, comprised of experienced scientists affiliated with prominent Dutch universities;

- independent assessment of study results by academics active in the same field, also known as 'peer-reviewed publications';

- audits by scientists, i.e. general on-site inspections of BPRC's scientific research programme, carried out by an independent party.

-

What is BPRC doing to promote research that does not involve animal testing?Everybody wants to reduce the number of studies involving animal testing. We do, too. For this reason, we are conducting a lot of research on alternative testing methods, based on the principles of reduction, refinement and replacement.

At BPRC, research geared towards the development of methods not involving animal testing has been assigned to a special independent research group. In addition, we promote and support the use of alternative methods in all our individual research units. -

What does BPRC's research mean to the species?Several primate species living all over the world are endangered. BPRC researchers are seeking to develop methods that will help us protect various primate species from extinction in an animal-friendly manner. Recently, these efforts have resulted in this new technology.

-

Do other organisations benefit from your research, as well?Absolutely. They benefit through our biobank, which is Europe's largest biobank for non-human primate cells and tissues. It is a good example of international scientific research carried out in accordance with the highest ethical standards. Through our biobank we store and distribute a wide range of biological materials, including tissues, products derived from serum, blood, DNA, RNA and B cells.

In this way, BPRC makes rare and valuable primate specimens available to both BPRC employees and external scientists. Our biobank may serve as an alternative source of information that will help people investigate scientific hypotheses and pathomechanisms, and test new bioactive substances and biological products. The idea is to minimise the level of discomfort experienced by the animals and to reduce our research expenditures.

-

-

About our animal testing policy

Questions about our animal testing policy

We seek to contribute to the development of new medications or therapies for serious diseases. In certain cases, animal testing is required for the proper performance of our research duties. When BPRC conducts experiments involving animal testing, we act in accordance with the Dutch Experiments on Animals Act (WOD), under which primates must only be used for biomedical research on serious diseases if no alternative methods are available. We operate in accordance with the principle of the three Rs: Reduction, Refinement and Replacement of experiments involving animal testing.

-

So what does this mean in actual practice?The principle of the three Rs basically amounts to our being able (thanks to new technologies and improved selection methods) to minimise the number of animals we need for testing purposes and to our seeking to make our primates' lives as pleasant as possible. In this way, we seek to obtain more information from fewer animals, meaning we will need fewer laboratory animals (reduction). In addition, we expend a great deal of energy on identifying methods that allow us to carry out research that does not require any animal testing (replacement). Furthermore, we pay a great deal of attention to ‘ethological research’, i.e., observation (which helps us give our primates even better living conditions) and animal training (which helps us reduce the level of anxiety experienced by our animals) (refinement).

-

How many primates live at BPRC?BPRC accommodates three types of monkeys: rhesus macaques, crab-eating macaques and marmosets. The majority of our approximately 1,000 animals are part of a breeding programme and are not used for experimental purposes. The great majority of our animals are rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). These animals are unique, because they have been indexed for a large number of genetic, virological and immunological characteristics. This allows us to carefully select the right animals for the right experiments, which in turn allows us to minimise the number of monkeys required for each particular experiment to the best of our ability.

-

Where does BPRC get its monkeys?All of BPRC's rhesus macaques, crab-eating macaques and marmosets were bred by ourselves. While this is expensive, it renders stressful transportation from breeding centres in countries such as China and Mauritius unnecessary. Occasionally we will buy a few monkeys from other specialist breeding centres in Europe when, in exceptional cases, we need more monkeys of a particular type than we have bred ourselves, or whenever we need new blood. We NEVER purchase monkeys that were caught in the wild. BPRC strictly complies with EU legislation.

-

Are all your monkeys used for experimentation purposes?No, only about 10% of our monkeys will be used in any given year. They will never be under the age of 4 (rhesus and crab-eating macaques) or 1.5 (marmosets). Generally, young animals stay in their birth groups until they reach those ages. These are the ages at which they will migrate to other groups in the wild. In this way we seek to imitate natural patterns to the maximum degree possible.

-

What benefits does this method have?The approach described above reduces the amount of anxiety experienced by the animals during experiments, since they are more mentally stable than animals which were removed from their birth group at an early age. The colony's manager (an animal behaviour expert), vets and geneticists closely cooperate to ensure that the animals are bred properly, to prevent inbreeding and to guarantee the best possible selection of animals for the various studies.

-

Why do you use monkeys rather than rats or mice?Genetically, monkeys are the species most similar to human beings; rhesus macaques are genetically about 93% identical to humans. It should be noted that not all primates are suitable for all studies. A primate's suitability for a particular study depends on many factors. The decision as to which animals are suitable for which studies is made by the colony's manager, in association with our vets. The females in the colonies have a 50% chance they will never be used for any experiments, since they may be necessary for breeding purposes.

-

What happens to the animals after an experiment?Generally speaking, the animals' organs must be examined at the end of a study. If this is not the case, we may in some cases be able to use the animals in a different study, always taking into account applicable laws and the level of discomfort caused to the animals. Most primates used in a study will eventually be euthanised, either for study-related purposes or for animal welfare reasons. Legislators check annually how many animals we have used for experimentation purposes.

-

What happens to the animals after they die?We collect the tissues and organs of every dead monkey. These materials are stored in our biobank, which is Europe's largest biobank for non-human primate cells and tissues. Scientists from all over the world are welcome to use these cells and tissues to examine alternative research methods.

-

Does BPRC conduct research on behalf of make-up companies, too?BPRC does not conduct research related to the development of cosmetics (this is prohibited under the Dutch Experiments on Animals Act), recreational drugs or weapons. BPRC only conducts research on diseases threatening the lives of humans.

-

-

Regarding animal welfare

Frequently asked questions about animal welfare

BPRC has an excellent reputation when it comes to knowledge, colony management and accommodating and looking after the animals. We apply sophisticated methods to minimise the discomfort experienced by the animals to the maximum extent possible, and we have a transparent policy with regard to animal welfare. We do so because we feel that our monkeys deserve to lead the most comfortable lives we are able to offer them. This means that they must be able to engage in the kind of behaviour that comes natural to their species.

-

How does BPRC accommodate its monkeys?Thanks to a major grant by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, we were able to create (in close consultation with animal welfare experts!) large group cages that enable us to breed the animals. As a result, our animal enclosures have been completely overhauled, and nearly all of BPRC's monkeys now live in a spacious and modern environment where they can be sociable. In addition to the large colonies used for breeding purposes, BPRC has equipped the units where the experiments are carried out with large cases in which the animals can live together and be sociable. Moreover, our animal behaviour experts keep a daily eye on the accommodations and on the composition of the social groups.

-

Do BPRC's monkeys lead terrible lives?We will continue, to the best of our ability, to give our animals pleasant lives for as long as animal testing continues to be necessary. We use animals for experimentation purposes so that we can contribute to the development of vaccines and medications against life-threatening diseases that occur worldwide. However, we do ensure that the animals used for these experiments lead the best lives we are able to give them. Since they are bred to be used in scientific projects, they deserve good lives, and we try every day to give them these good lives. For this reason, they spend the first years of their lives (four years for rhesus and crab-eating macaques, 1.5 years for marmosets) in their birth group. Many of our monkeys are never used in experiments in the first place.

-

How do you go about making the animals' lives as pleasant as possible?The outdoor enclosures are large cages in which the monkeys have plenty of room to move freely and play to their hearts' content. In order to ‘enrich’ their lives, we give them many toys and pieces of equipment, such as fire hoses, roosts for them to sit on, balls, trapezes and mirrors.* Our animal care workers have actually won awards for their continued efforts to ensure that BPRC's monkeys have the best possible living conditions. Another major component of our policy is so-called 'food enrichment'. This means that we offer animals who are subject to an experimental protocol something new every day, ranging from icecream to food puzzles. We described and explained all forms of environmental enrichment used at BPRC for the various species of monkeys in the 'Enrichment Manual for Macaques and Marmosets' we drew up in association with EUPRIM-NET. Research institutes from all over the world have requested copies of this manual, so that they, too, can successfully provide their animals with pleasant lives. The document can be downloaded here.

* In the past several organisations donated materials that could be used for environmental enrichment purposes (e.g. old tennis balls, tyres, ropes, fire hoses). These materials were donated by organisations such as schools, sports clubs and fire brigades. BPRC continues to appreciate donations to its fund for environmental enrichment.

-

How do you prepare your monkeys for experiments?BPRC has engaged in animal training, designed to get the animals to cooperate with scientists of their own accord, for quite a few years now. The purpose of this training is to ensure that the experiments can be carried out in a smooth and anxiety-free manner, where possible. For this reason, animal training is an important part of our enrichment strategy. If our animals can be taught to cooperate (for instance, by shaking a human's hand), they will experience less anxiety during the performance of certain procedures. By means of so-called ‘Positive Reinforcement Training’ (PRT) we reward our animals for their good behaviour (e.g. by giving them peanuts and raisins) and ignore their poor behaviour. This highly effective method is based on animals' natural ability to learn from their experiences.

-

Do your monkeys suffer a great deal of discomfort?Animal testing is subject to stringent regulations in the Netherlands. Severe suffering is not tolerated. After all, every animal has the right to a life with as little pain and anxiety as possible. If animals are expected to suffer severe discomfort in a new study, the study will quite simply not be conducted. The Central Authority for Scientific Procedures on Animals (CCD) (an external organisation) weighs the study's scientific importance against the level of discomfort expected to be experienced by the animals. Studies must be designed in such a way as to keep animal suffering to an absolute minimum. Our animal care workers play a part in this process, by training the monkeys to accept research settings so as to prevent anxiety. Our vets seek to find better ways to interact with the monkeys every day.

-

What do we mean when we say 'discomfort'?Discomfort is a lack of well-being in the broadest sense of the word. It may include pain and illness, as well as anxiety or the lack of natural living conditions. Despite the fact that ‘discomfort’ is a broad concept, we do keep track of the level of discomfort experienced by our animals, using a scoring system. Under previous animal testing legislation, our scoring system involved a scale from 1 to 6. Under the new Dutch Experiments on Animals Act 2014, we must characterise the various levels of discomfort as mild, moderate, severe or extremely severe.

-

Can you be an animal lover if you work at BPRC?You bet! It is actually our animal care workers who make the difference to our monkeys. They try to make the lives of our monkeys as good and entertaining as possible. They inevitably end up loving the animals and do not like to send them into experiments, even though they understand why it is necessary to do so. We accommodate and look after our animals with devotion and attention, and while we do so, we try to determine how we can change things in the future. To this end, BPRC makes a very active contribution to the development of methods that may be able to replace animal testing.

-

Can I get a tour of your premises?You are welcome to come and see us at BPRC. Upon request, we will give school classes, students and groups of other interested parties a tour of our premises. Many reports of such visits can be found on the Internet. We often receive visits from ministers, state secretaries and other policy makers, who are welcome guests at BPRC. Each year, BPRC receives more than 600 visitors.

-

If we join a tour, will we see all of your company?Technically, yes, but we do not like exposing the animals at our experimental units to a high level of anxiety by allowing people they do not know into their environment. Moreover, people visiting the closed environment (where we prepare the animals for the experiments and where they are examined) must have undergone tuberculosis screening, because the animals are susceptible to TBC. In addition, people must change out of their own clothes, wear mouth caps and possibly take a shower. We take these precautions because these animals are susceptible to some of our diseases.

-

-

Regarding collaborative partnerships

Frequently asked questions about partnerships

BPRC is outwardly oriented and often receives requests for collaboration from other organisations. We have collaborative partnerships with many other organisations, both within and outside our own industry, ranging from universities and hospitals to zoos and other primate research centres. We also receive funds from scientific foundations such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research, who believe that our research may make a significant contribution to the objectives they seek to achieve.

-

How do all these partnerships benefit BPRC?Everything we do revolves around science, public health and animal welfare. Every grant we receive from the government or a scientific foundation contributes to the development of new medications, the improvement of public health, increased knowledge of monkeys and improved primate welfare, all over the world! We share our knowledge with other parties who conduct research on human and animal health.

-

Is your research of any use to animals living outside BPRC?It certainly is. Animals kept in zoos and even animals living in the wild benefit from what we do. Our work does not just focus on improving people's health. We also focus on animal welfare. We have collaborative partnerships with zoos. In addition, BPRC contributes to the health of monkeys living in the wild by treating them against infectious diseases and genotyping individual animals, in order to prevent inbreeding among animals living in the wild and eradicate the diseases associated with this, among other things. BPRC researchers are working hard to develop methods which will help us preserve monkey species in an animal-friendly manner.

-

How do you contribute to other types of research?We do not keep the cells and tissues obtained in our studies (by means of animal testing or otherwise) to ourselves. We make material available to others through our biobank, which is Europe's largest biobank for non-human primate cells and tissues. It is a good example of international scientific research carried out in accordance with the highest ethical standards. Through our biobank we store and distribute a wide range of biological materials, including tissues, products derived from serum, blood, DNA, RNA and B cells. These cells and tissues are highly valuable to other research institutes, companies and organisations engaged in biomedical research.

In this way, BPRC makes rare and valuable primate specimens available to both BPRC employees and external scientists. Our biobank may serve as an alternative source of information that will help people investigate scientific hypotheses and pathomechanisms, and test new bioactive substances and biological products. The idea is to minimise the level of discomfort experienced by our animals and to reduce our research expenditures.

-

Do you collaborate with other institutes and other experts working in the field?BPRC has cross-border collaborative partnerships with several universities, research institutes and scientists. We are represented in both Dutch and international governing bodies active in the field of animal testing. Moreover, our animal care workers, vets and ethologists actively take part in national and international conferences, where they exchange experiences with their colleagues elsewhere. We are also actively involved in organisations such as the Biotechnical Society (Biotechnische Vereniging), the Dutch Society for Animal Testing (Nederlandse Vereniging voor Proefdierkunde) and the European Association of Veterinary Anatomists.

-

What are the results of all these collaborative partnerships?A contribution to the three Rs (reduction, refinement and replacement of experiments involving animal testing), i.e., a contribution to animal welfare. We contribute to improved animal welfare by focusing on proper nutrition, accommodations and care. By exchanging experiences with our colleagues in the field, we can make sure we are all on the same page when it comes to the methods and protocols used.

-

What is your collaboration with the animals themselves like?BPRC has engaged in animal training, designed to get to the animals to cooperate with scientists of their own accord, for quite a few years now. The purpose of this training is to ensure that the experiments can be carried out in a smooth and anxiety-free manner, where possible. This is beneficial both to animal welfare and to the studies we carry out. To this end, BPRC's animal trainers always use innovative methods to ensure that the studies are conducted in the best possible manner. Furthermore, our animal trainers are involved in international programmes designed to further develop these methods. They share their knowhow with other research institutes, by giving lectures or teaching workshops, among other things.

-

-

Regarding our monkeys

Frequently asked questions about our monkeys

Primates are mammals. All monkeys, apes and strepsirrhini are mammals. The scientific classification name 'primate' means 'first'. Human beings are primates too. For this reason, we distinguish between two types of primates: human primates (i.e., human beings) and non-human primates (apes and monkeys). BPRC houses three types of monkeys: rhesus macaques, crab-eating macaques and common marmosets.

-

What are rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta)?

Habitat

Rhesus macaques are native to the following Asian countries: Afghanistan, Northern India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Northern Thailand, Laos, Northern Vietnam and Southern China. They live in grasslands and woodlands and in mountainous regions up to 2,500 metres in elevation. They are also frequently spotted in cities and temple complexes. Rhesus macaques are able to survive in both cold and heat. In winter they have thicker fur. They generally live to be about 28, but some will be over thirty years old.

Physical characteristics

Rhesus macaques have reddish brown fur and much lighter-coloured bellies. Their faces are pink and bereft of fur. The females of the species may have red faces during their fertile periods. Adult animals measure up to 64 cm and have a tail measuring 18 to 30 cm. Males weigh approximately 10 kg, while females often weigh only half of that.

Behaviour

Rhesus macaques are excellent and fast climbers and also love swimming. They live in social groups comprised of eleven tot seventy animals, with the average troop being comprised of some twenty animals. Groups tend to consist mainly of females, with just a few males. Young males are raised by the entire group. They tend to leave their group at age 4 or 5. They will then fight other males to become the dominant male in another group, where they will mate and breed. Rhesus macaques are aggressive animals whose groups have a strict hierarchy.

Diet

Rhesus macaques mainly eat plant materials – generally herbs, but also leaves, needles and roots. They may also eat invertebrates or even small vertebrates or birds. Rhesus macaques have cheek pouches in which they can temporarily store food.

Reproduction

In Northern India, rhesus macaque procreation is seasonal. In warmer areas, they have young all year round. After a gestation period of 135 to 194 days, they will typically give birth to one young. Females reach sexual maturity at around three years of age, and tend to have their first young at age 4 or 5. Males are sexually mature at around age 4.

BPRC works with rhesus macaques because...

they are genetically 93% identical to humans. When it comes to the genes that are vital to the immune system, rhesus macaques' genes are an impressive 97% identical to humans'. By examining how monkeys' genes behave in certain situations, we can get a good idea of how the corresponding human genes would respond.

How rhesus macaques live at BPRC

Animals used for breeding purposes live in natural troops with the same composition as troops living in the wild. They live in large indoor and outdoor enclosures which have been equipped with climbing materials and toys. Monkeys which are being prepared for experiments receive extensive training. We use the fact that they are curious animals to familiarise them with experimental situations, always rewarding them for good behaviour.

Monkeys used for experimental purposes live in smaller enclosures, where animal care workers keep a close eye on their well-being. Monkeys never undergo experimentation alone. They are always joined by their friends and siblings. They are given many playthings, such as food jigsaw puzzles and materials that they can tear to pieces.

-

What are crab-eating macaques (Macaca fascicularis)?

Habitat

Crab-eating macaques are native to the tropical zones of South East Asia, e.g. Southern Myanmar, Thailand, Southern Laos, Cambodia, Southern Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines. They live in woodlands near rivers. They live high in the treetops as well as on level ground. They are also frequently spotted in cities and temple complexes.

Physical characteristics

Crab-eating macaques have greyish brown fur and much lighter-coloured bellies. They have brown faces that are partially covered in fur. They are easily recognisable by the small tuft of hair on their heads. Adult females will sometimes grow beards. Adult animals measure up to 50 cm and have a tail measuring 50 to 60 cm. Males generally weigh 6 to 8 kg, while females often weigh only half of that.

Behaviour

Crab-eating macaques are excellent and fast climbers and love swimming. They live in social groups which are typically comprised of some thirty animals. Groups tend to consist mainly of females, with just a few males. Young monkeys are raised by the entire group. They tend to leave their group at age 4 or 5. They will then fight other males to become the dominant male in another group, where they will mate and breed. Troops are subject to a strict hierarchy.

Diet

Crab-eating macaques mainly eat fruit. In addition, they like leaves, buds, grass, flowers, seeds, insects, shrimp, frogs and, as their name suggests, crabs.

Reproduction

Crab-eating macaques mate and breed all year. Once every year or every two years they will give birth, typically to one young. Females reach sexual maturity at about age 4. Crab-eating macaques generally live to be 30-35 years of age.

BPRC works with crab-eating macaques because...

... animal behaviour experts study our social groups of crab-eating macaques on a daily basis. In this way, we learn much about their behaviour. Furthermore, because we are gaining a better understanding of them, we are better able to prevent them from experiencing anxiety during experiments. In addition, their behaviour teaches us more about human social behaviour. We sometimes use crab-eating macaques for biomedical experimentation purposes. How crab-eating macaques live at BPRC Animals used for breeding purposes live in natural troops with the same composition as troops living in the wild. They live in large indoor and outdoor enclosures which have been equipped with climbing materials and toys. Monkeys which are being prepared for experiments receive extensive training. We use the fact that they are curious animals to familiarise them with experimental situations, always rewarding them for good behaviour. Monkeys used for experimental purposes live in smaller enclosures, where animal care workers keep a close eye on their well-being. Monkeys never undergo experimentation alone. They are always joined by their friends and siblings. They are given many playthings, such as food jigsaw puzzles and materials that they can tear to pieces.

-

What are common marmosets (Callitrix jacchus)?

Habitat

Common marmosets are native to the northeastern coast of Brazil. They typically live in the jungle. Due to the release of captive individuals, they have spread to Rio de Janeiro.

Physical characteristics

The pelage of these small monkeys is multi-coloured, being sprinkled with brown, grey, yellow and white. They have a long banded tail, as well as white ear tufts. Their snouts are pink but turn to dark brown near the nose when they have had too much sun. Adult animals measure up to 19 cm and have a tail measuring 20 to 25 cm. They weigh about 300-400 grams.

Behaviour

Marmosets live in stable extended families, typically comprised of about nine animals. Groups consist of one or two breeding females and one breeding male, along with their offspring and parents. Sometimes marmosets will leave their birth group once they are adults. The breeding male and female are the dominant members of the group. Apart from this, the social hierarchy is age-based. Marmosets generally live to be 12 to 15 years old.

Diet

Marmosets mainly eat tree exudates, fruit, insects, seeds, flowers, snails, lizards and eggs.

Reproduction

Marmosets live in stable extended families. Generally, there will be one monogamous breeding pair that will give birth to young (often twins). The female will typically fall pregnant again soon after giving birth. Young are carried around by their father and siblings.

BPRC works with marmosets because...

... marmosets are susceptible to the onset of several serious human diseases, such as MS, Parkinson's and Alzheimer's. In addition, these small animals are quite capable of learning several tasks, thus allowing us to quickly recognise abnormalities following the onset of the disease. This in turn allows us to perform thorough assessments of new medications or therapies.

How marmosets live at BPRC

Animals used for breeding purposes live in natural troops with the same composition as troops living in the wild. They live in large indoor and outdoor enclosures which have been equipped with climbing materials and toys. Monkeys which are being prepared for experiments receive extensive training. We use the fact that they are curious animals to familiarise them with experimental situations, always rewarding them for good behaviour. Monkeys used for experimental purposes live in smaller enclosures, where animal care workers keep a close eye on their well-being. Monkeys never undergo experimentation alone. They are always joined by their friends and siblings. They are given many playthings, such as food jigsaw puzzles and materials that they can tear to pieces.

Left: crab-eating macaque, top: rhesus macaque, right: common marmoset.

-