Tuberculose

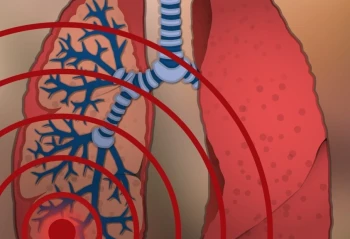

Tuberculosis continues to be one of the most serious infectious diseases in the world. It is estimated that one person dies every twenty seconds due to the consequences of infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Moreover, approximately one quarter of the world's population have been infected without realising it, meaning that a new outbreak could happen any time. New therapies must be developed as a matter of urgency.

An effective vaccine against the consequences of infection at a young age has been on the market for several decades now: BCG (Bacille Calmette-Guérin). However, this vaccine has been found to be insufficiently effective against life-threatening tuberculous pneumonia at a later age. Moreover, this vaccine can cause severe adverse reactions in people with impaired immune systems. In addition, antibiotic-resistant strains of TB are increasingly common. As a result, we are finding it increasingly hard to treat the disease.

Why we need better medications

Although antibiotics are available on top of the BCG vaccine, infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis requires treatment that will take many long months (as opposed to just a few days). Therefore, we urgently need a better vaccine (or vaccine programme) to combat tuberculosis, both with a view to prevention and with a view to curing the disease (therapy).

It is clear that we need better medications. However, it is proving quite hard to develop effective therapies quickly. What is stopping us is 1) a limited understanding of the mechanisms protecting host humans from TB, and 2) the various immunoevasive strategies of the pathogen, Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Many of these issues can be solved by using an animal model.

The predictive power and development of new medications

Macaques may play a vital part in our studies focusing on the prevention and treatment of TB. Macaques are very similar to humans, in terms of their immune system, but particularly in terms of their susceptibility to tuberculosis and the way in which the disease presents, which is similar to the way it presents in humans. The BCG vaccine's protective effect appears to be as variable in monkeys as it is in humans. For this reason, macaques have greater predictive power for humans in this case than any other animal model.

Both in human beings and in non-human primates, the BCG vaccine suppresses the disease, but does not protect us from being infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In other words, we should probably seek to develop a better vaccine or different type of therapy. Monkeys give us the opportunity to evaluate the efficacy of such new therapies or vaccines in a model that resembles human beings.

Greater understanding

Following extensive preliminary studies, BPRC assesses potential vaccines in primate models for safety (are there any adverse reactions?), immunogenicity and protective efficacy. These studies allow us to examine the complex host-pathogen interaction under controlled conditions. Using the results of these studies and our improved understanding of this infectious disease, we seek to contribute to the development of improved therapies.

Why we need monkeys for our studies

In some TB studies, monkeys are the most useful animal models. Pursuant to Dutch law, monkeys can only be used as experimental animals when no alternative method exists.