At BPRC we study which cells are essential for the fight against infections and how we can stimulate these cells to swing into action. Modern equipment helps us in doing so, allowing us to collect more and more data from fewer animals. And this is important for animal research.

One of the latest additions to our laboratory is a new flow cytometer, which is a machine that is very good at recognizing the different types of immune cells (lymphocytes) in our body. This is not an easy task, because in our blood alone we have about a billion lymphocytes. All of them have their specific characteristics and functions.

Explorers, soldiers, snipers and spies

We sometimes compare our immune system with an army of soldiers that wages war against bacteria or a virus. At the start of the war, you need explorers who are trained to crawl through mud in camouflage gear, followed by soldiers with a lot of bombs and grenades for the big battle. When most of the enemy has been taken out, you just need a few snipers on the roof. After the war is over, it can be useful to deploy spies, who can scout the area with a picture of the enemy in their hand and at the first sign of trouble immediately can summon a whole army. In blood, those spies are called memory cells. And those are the cells in blood that hopefully will be generated after vaccination. Blood is packed with those spies: a few for last year’s common cold, the chickenpox, the flu, food poisoning, but also for instance, for the measles. Even if you have never picked up the measles, but were vaccinated.

Immune cells are not only present in blood but also, for example, in our respiratory tract. Besides immune cells in camouflage gear, there are other soldiers at work here: the alveolar macrophages. These big giants are specific to the respiratory tract and clean up everything that they come across. They play an important role in respiratory tract infections.

Which lymphocytes are important at what point?

Every infectious disease requires a unique action plan. With a flow cytometer, we can identify the strategies down to the smallest detail and differentiate between the successful and less successful action plans. This information is important for the development of better vaccines. Unfortunately, we are unable to study this in humans because we usually do not exactly know when an infection in humans has occurred and at what stage the action plan of the immune system is in.

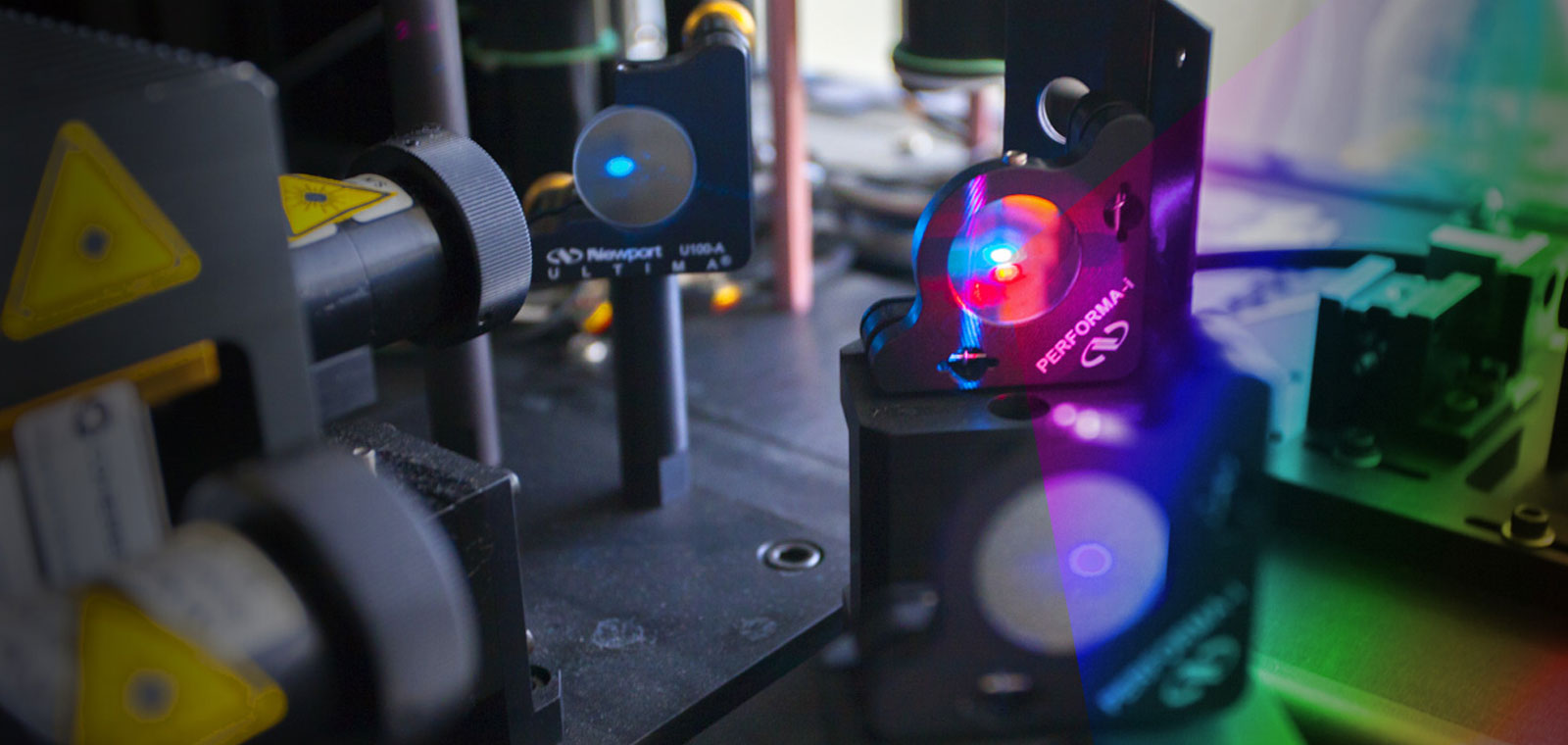

How flow cytometry works

In a flow cytometer we let immune cells suspended in a fluid pass through a laser beam. This happens at a speed of thousands of cells per second. A flow cytometer can identify the cells based on shape and size, but can also discriminate cells between type, function and state. We do the latter by labelling cell surface molecules with fluorescent markers. When different colours are simultaneously used for different molecules, a kind of fingerprint is created. This fingerprint says something about the function of the immune cell.

The advantage of the new machine

Our new flow cytometer can measure more colours at the same time, about three times as much as the previous one. This way, we can gather more data and therefore more knowledge using fewer animals. Also, we can better study the function of certain immune cells in respiratory tracts after a disease caused by infection with, for example, bacteria (tuberculosis) or a virus (corona).